CEO Playbook

CEO Playbook

CEO Playbook

CEO Playbook: AI Strategy

Most Digital & AI strategies fail because organisations pick technology first, then work out what to do with it. This playbook shows you how to work backwards from your goal, mapping what needs to happen across your business before you buy a single tool.

1. Why AI Strategies Fail

You probably need an AI strategy. You might already have one that isn't working. Or you might be stuck at the starting line, unsure where to begin.

The common problem is the same: organisations start with technology instead of strategy. Someone hears about AI at a conference and comes back excited. Leadership decides "we need to do something with AI." The question becomes "what tools should we buy?" not "what are we actually trying to achieve?"

This is backwards. AI is not a strategy. It's a tool that might help you execute a strategy if you have one. But most organisations don't have a clear goal. They have vague aspirations like "improve efficiency" or "become more data-driven" that mean nothing specific.

Here's what usually happens. Leadership forms an AI committee. The committee produces a document about innovation and transformation. Maybe they buy some tools. Twelve months later, nothing has changed. Someone points out they've spent money and have nothing to show for it. The cycle repeats.

The problem isn't the technology. The problem is lack of strategic clarity. If you cannot articulate what winning looks like in specific, measurable terms, no amount of AI will help you. "Improve efficiency" is not a goal. "Reduce invoice processing time from 5 days to 24 hours" is a goal.

The second problem is that AI strategies ignore culture. Buying tools is easy. Getting people to change how they work is hard. Getting them to trust a system instead of their spreadsheet is hard. Getting senior people to admit they don't understand something is hard.

Most AI strategies pretend this doesn't exist. They focus on technology selection and implementation timelines. They produce Gantt charts and milestone plans. They skip over the uncomfortable bit where someone has to explain that projects don't fail because of budget, they fail because of how people actually work.

You need a different approach. One that forces you to define what you're trying to achieve before anyone mentions technology. One that makes you map out what has to change about how people work, not just what tools you'll buy. That's what the Strategy Canvas does.

1. Why AI Strategies Fail

You probably need an AI strategy. You might already have one that isn't working. Or you might be stuck at the starting line, unsure where to begin.

The common problem is the same: organisations start with technology instead of strategy. Someone hears about AI at a conference and comes back excited. Leadership decides "we need to do something with AI." The question becomes "what tools should we buy?" not "what are we actually trying to achieve?"

This is backwards. AI is not a strategy. It's a tool that might help you execute a strategy if you have one. But most organisations don't have a clear goal. They have vague aspirations like "improve efficiency" or "become more data-driven" that mean nothing specific.

Here's what usually happens. Leadership forms an AI committee. The committee produces a document about innovation and transformation. Maybe they buy some tools. Twelve months later, nothing has changed. Someone points out they've spent money and have nothing to show for it. The cycle repeats.

The problem isn't the technology. The problem is lack of strategic clarity. If you cannot articulate what winning looks like in specific, measurable terms, no amount of AI will help you. "Improve efficiency" is not a goal. "Reduce invoice processing time from 5 days to 24 hours" is a goal.

The second problem is that AI strategies ignore culture. Buying tools is easy. Getting people to change how they work is hard. Getting them to trust a system instead of their spreadsheet is hard. Getting senior people to admit they don't understand something is hard.

Most AI strategies pretend this doesn't exist. They focus on technology selection and implementation timelines. They produce Gantt charts and milestone plans. They skip over the uncomfortable bit where someone has to explain that projects don't fail because of budget, they fail because of how people actually work.

You need a different approach. One that forces you to define what you're trying to achieve before anyone mentions technology. One that makes you map out what has to change about how people work, not just what tools you'll buy. That's what the Strategy Canvas does.

1. Why AI Strategies Fail

You probably need an AI strategy. You might already have one that isn't working. Or you might be stuck at the starting line, unsure where to begin.

The common problem is the same: organisations start with technology instead of strategy. Someone hears about AI at a conference and comes back excited. Leadership decides "we need to do something with AI." The question becomes "what tools should we buy?" not "what are we actually trying to achieve?"

This is backwards. AI is not a strategy. It's a tool that might help you execute a strategy if you have one. But most organisations don't have a clear goal. They have vague aspirations like "improve efficiency" or "become more data-driven" that mean nothing specific.

Here's what usually happens. Leadership forms an AI committee. The committee produces a document about innovation and transformation. Maybe they buy some tools. Twelve months later, nothing has changed. Someone points out they've spent money and have nothing to show for it. The cycle repeats.

The problem isn't the technology. The problem is lack of strategic clarity. If you cannot articulate what winning looks like in specific, measurable terms, no amount of AI will help you. "Improve efficiency" is not a goal. "Reduce invoice processing time from 5 days to 24 hours" is a goal.

The second problem is that AI strategies ignore culture. Buying tools is easy. Getting people to change how they work is hard. Getting them to trust a system instead of their spreadsheet is hard. Getting senior people to admit they don't understand something is hard.

Most AI strategies pretend this doesn't exist. They focus on technology selection and implementation timelines. They produce Gantt charts and milestone plans. They skip over the uncomfortable bit where someone has to explain that projects don't fail because of budget, they fail because of how people actually work.

You need a different approach. One that forces you to define what you're trying to achieve before anyone mentions technology. One that makes you map out what has to change about how people work, not just what tools you'll buy. That's what the Strategy Canvas does.

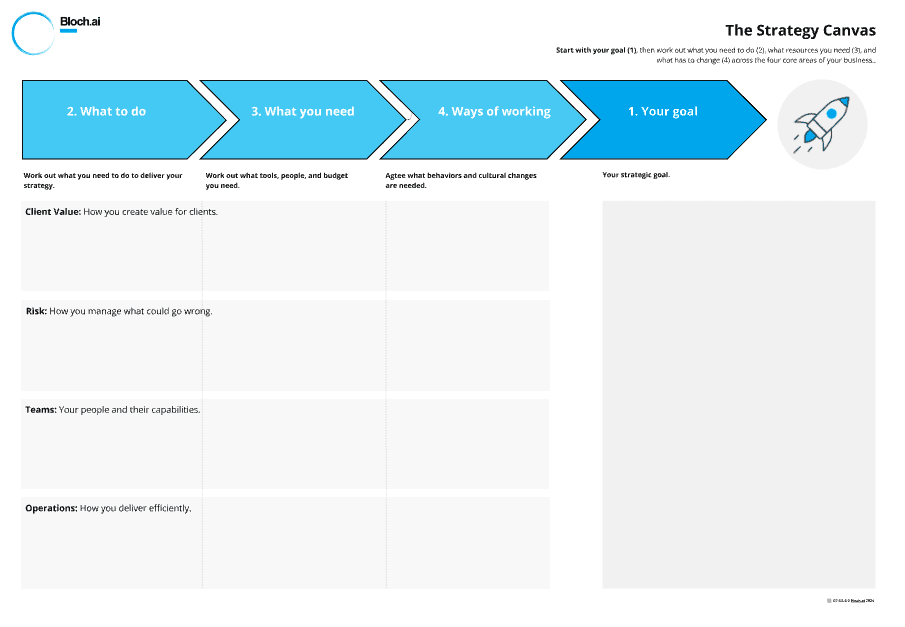

2. Introducing the Strategy Canvas

The Strategy Canvas is a planning tool that forces you to work backwards from your goal. Most organisations do this the wrong way round. They pick technology, then work out what to do with it. This canvas makes you start with where you want to get to. Only then do you figure out what you need to do, what resources you need, and what has to change about how people actually work.

Click Here: It is available here on the Miroverse.

Why a canvas? Why a workshop?

Strategy doesn't happen in isolation. It happens through conversation, debate, and honest assessment of what's actually possible. A strategy document written by one person and presented to leadership rarely survives contact with reality. It gets nodded at, filed, and forgotten.

A workshop forces the conversation to happen. It gets decision-makers in a room together, looking at the same information, making trade-offs in real time. The canvas gives structure to that conversation so it doesn't devolve into unfocused debate about everything at once.

The visual nature matters. Post-it notes on a wall (or a Miro board) let everyone see the whole picture simultaneously. You can spot gaps, dependencies, and contradictions that aren't obvious in a written document. When someone says "we need better data" and you look at the canvas and see they haven't identified who will clean that data or how people will be trained to use it, the gap becomes obvious.

How this works in practice

When we run this for clients, we don't just turn up with a blank canvas and hope for the best. We recommend spending a few days beforehand understanding the business. Talk to people individually - leadership, technical staff, whoever will be involved in executing whatever comes out of the workshop. Ask about previous initiatives that failed and why. Look at what's already been tried. Identify the political dynamics and sacred cows.

This pre-work serves two purposes. First, it means the workshop is productive from minute one because you're not spending the first hour just establishing context. Second, you spot the gaps between what people say publicly and what they say privately. That tells you where the difficult conversations need to happen.

The workshop itself is where the canvas gets filled out. A good facilitator will push for specificity and make sure the uncomfortable topics don't get sidestepped. Afterwards, spend a couple of days producing a clear deliverable - the completed canvas, a prioritised action plan, and an honest assessment of what the real blockers are.

If you're running this internally, the same principles apply. Do the pre-work. Make sure you have the right people in the room. Don't rush the process. And be prepared for the conversation to get uncomfortable - that's usually a sign it's working.

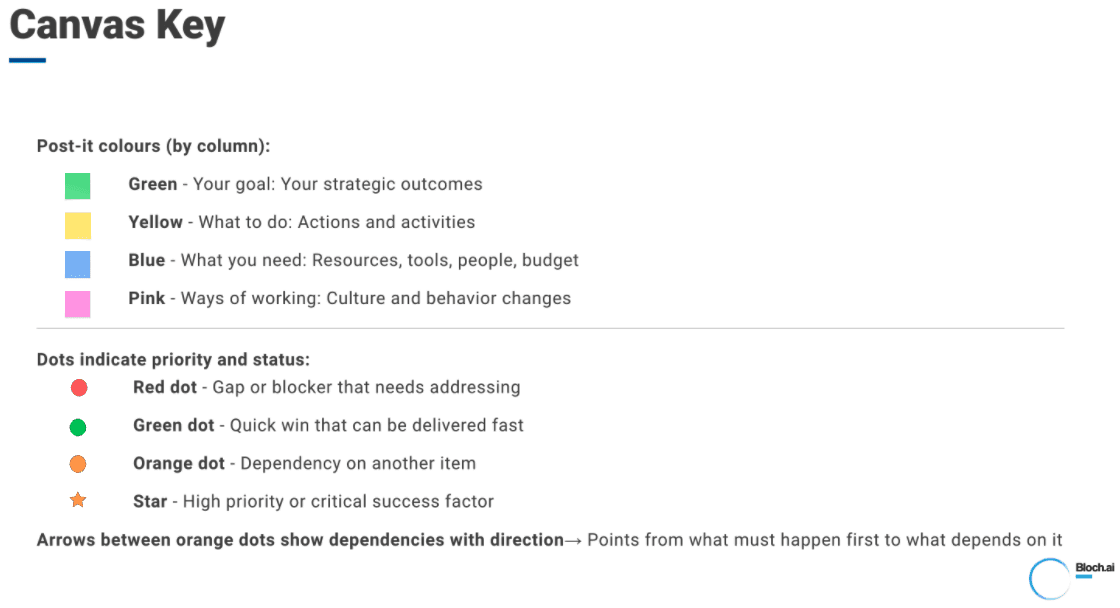

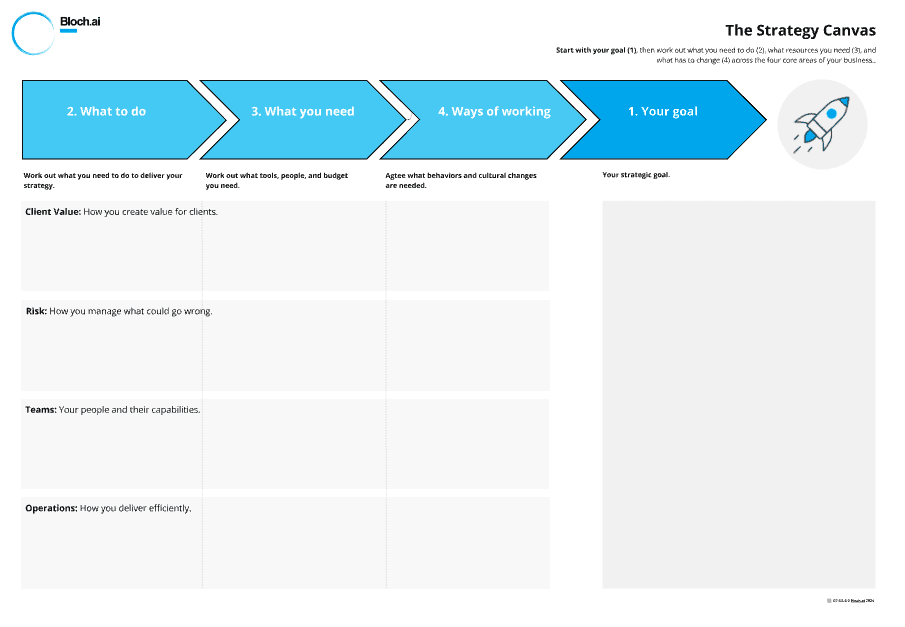

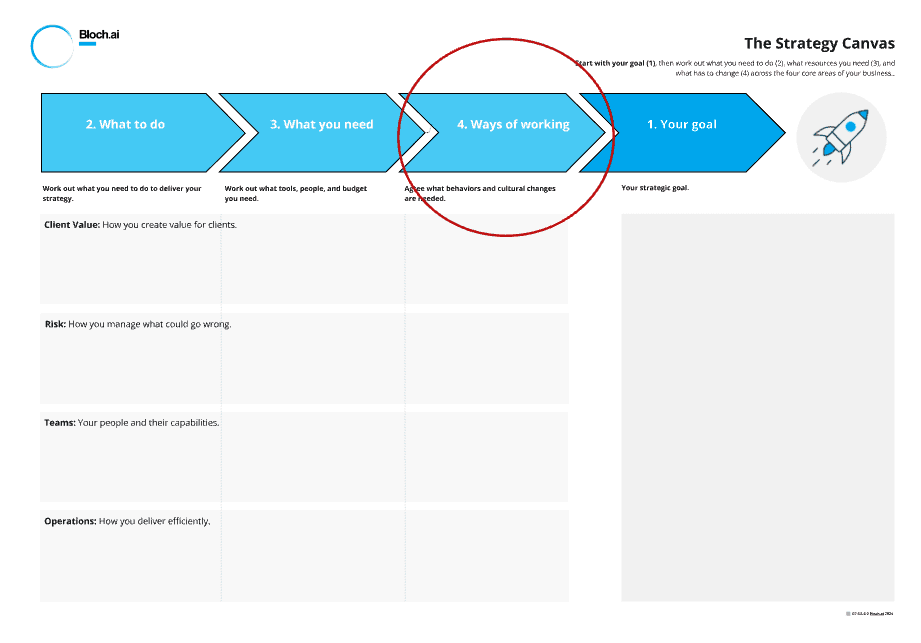

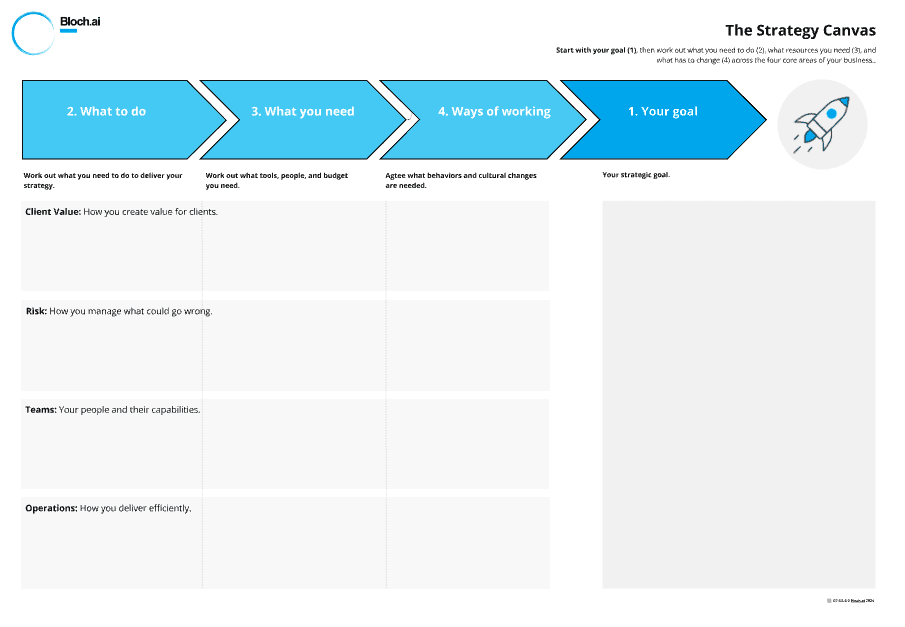

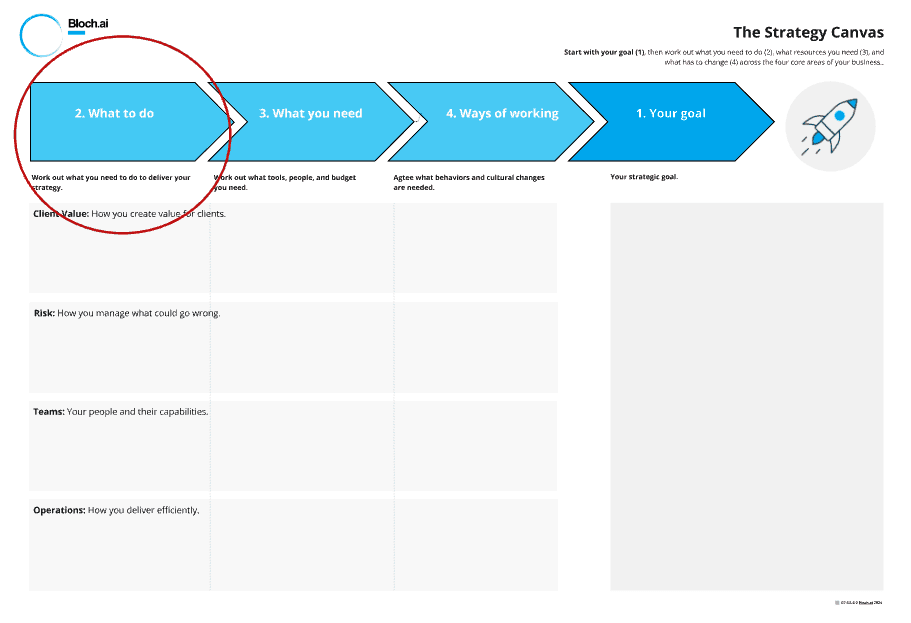

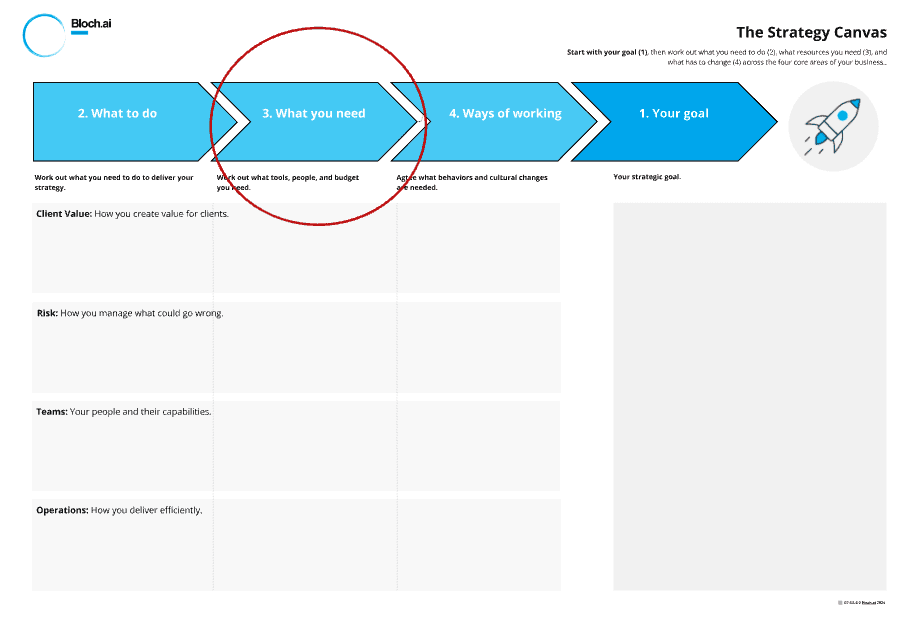

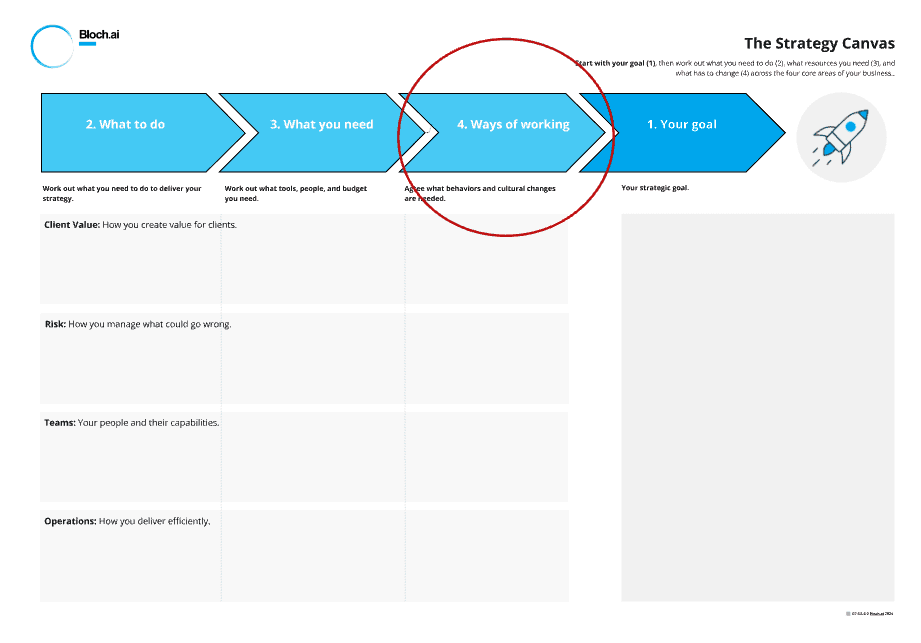

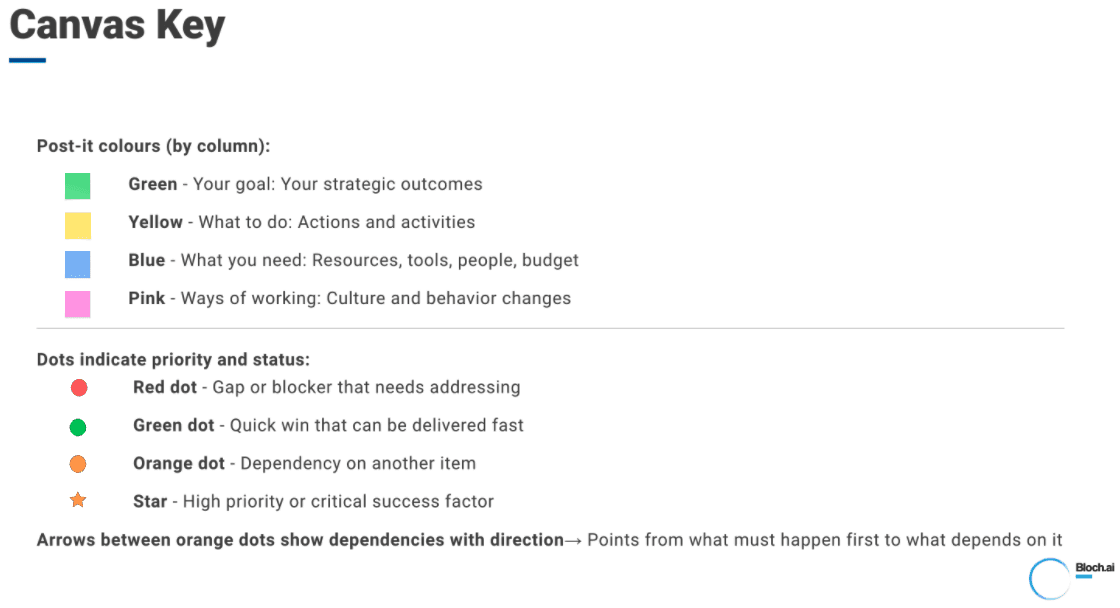

What the canvas looks like

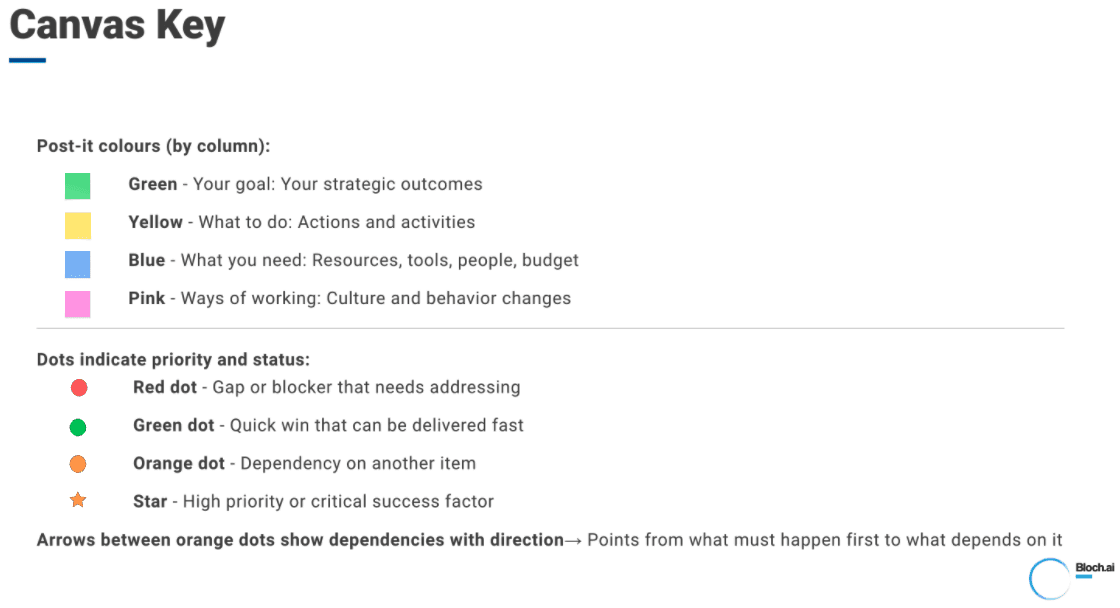

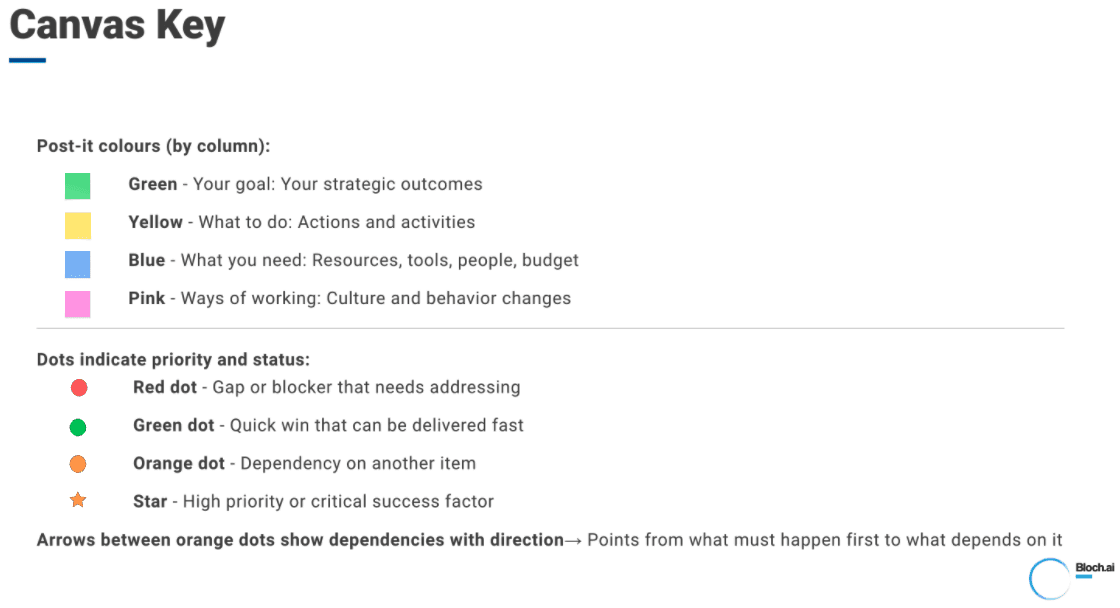

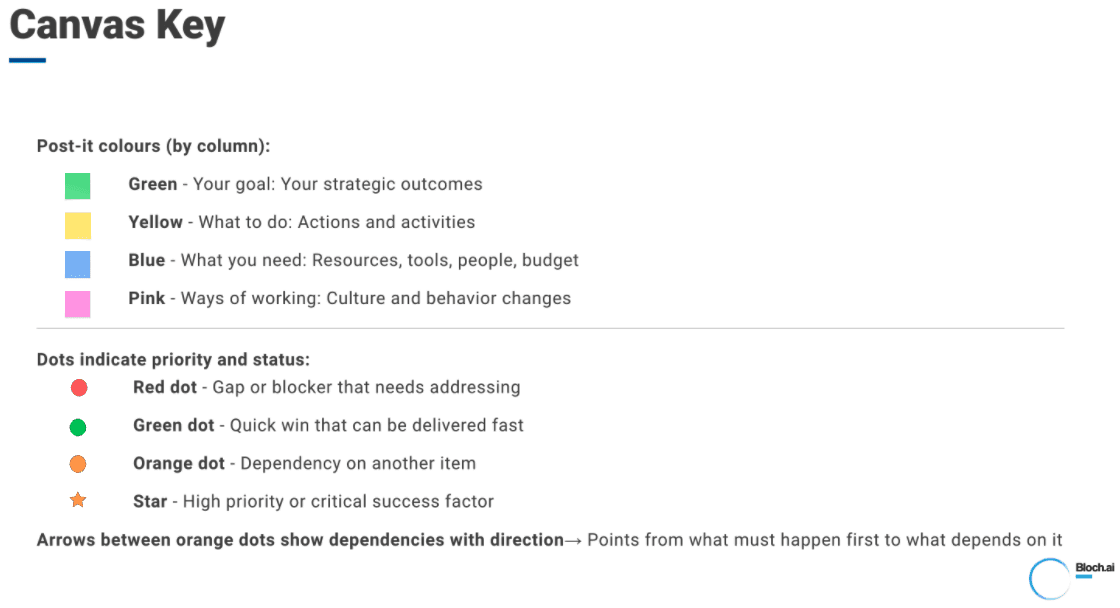

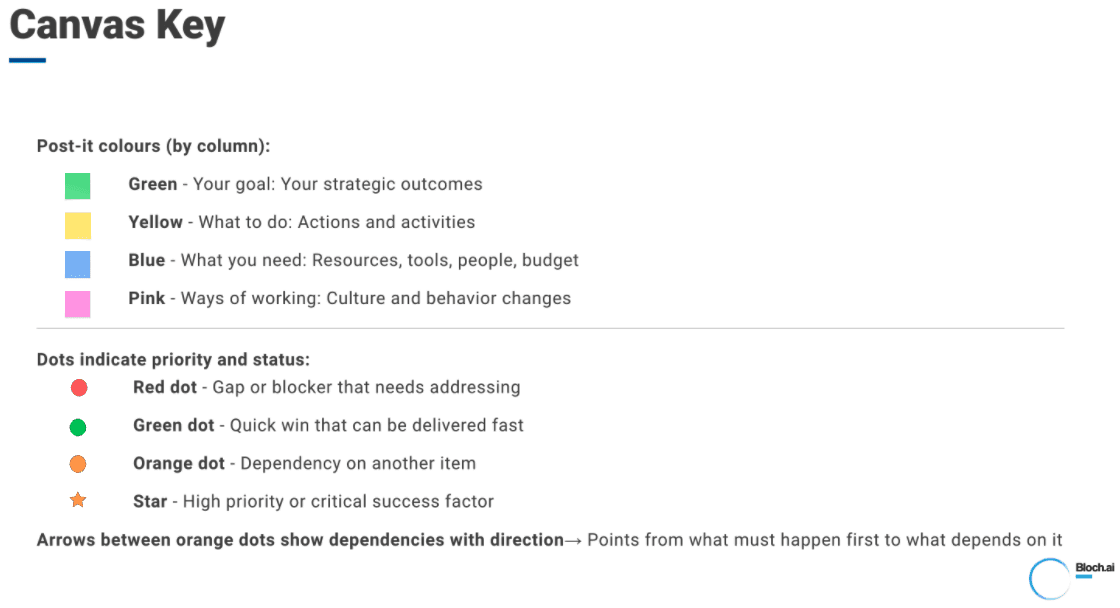

The canvas is a single page divided into four columns that move from right to left. On the right: your goal, written on a green post-it note. Moving left, three columns: what to do (yellow notes), what you need (blue notes), and ways of working (pink notes). Each column asks a specific question and forces specific thinking.

It covers four areas of any business:

Client Value (how you create value for clients)

Risk (how you manage compliance, controls, and regulation)

Teams (your people and their capabilities)

Operations (how you deliver efficiently)

Every action, every resource requirement, and every cultural change maps to one of these four areas. This structure stops you missing critical pieces. You might remember to think about operations but forget about risk. You might focus on client value but ignore team capabilities. The four areas make sure you think through the whole business.

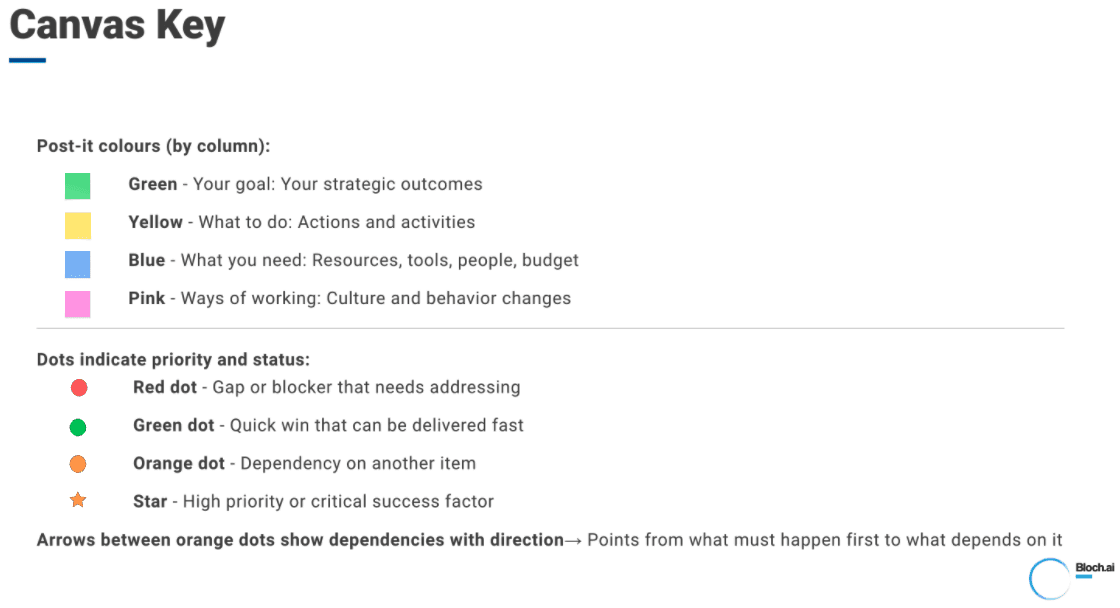

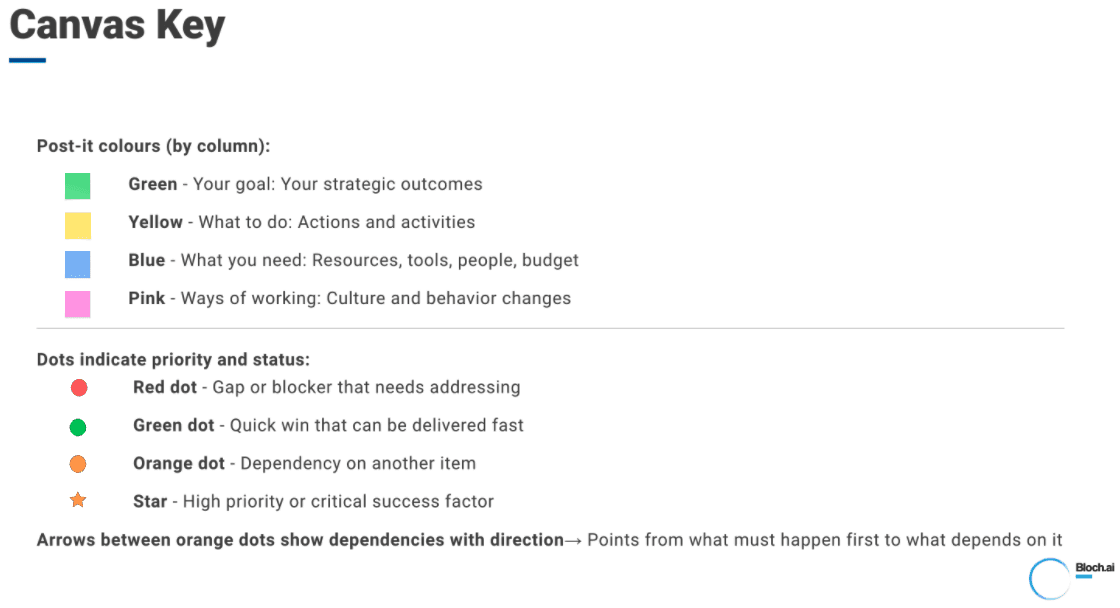

The canvas uses coloured post-it notes to distinguish between different types of thinking. Green for your goal. Yellow for actions. Blue for resources. Pink for behaviour and culture changes. This visual system keeps conversations focused and stops people jumping between "what we want to achieve" and "what tools we should buy" as if they are the same question.

Once you've filled the canvas with post-its, you add dots and arrows. Red dots mark gaps or blockers. Green dots mark quick wins. Orange dots show dependencies - where one thing must happen before another. Stars indicate critical success factors. Arrows between orange dots show the sequence. This layer turns the canvas from a list of ideas into a prioritised plan.

You can use this for enterprise-wide transformation or a single department initiative. The scale changes but the logic stays the same. Define what winning looks like, work backwards to what needs to happen, be honest about what has to change.

Using this guide

This guide gives you everything you need to run this yourself. The framework is simple; the hard part is getting senior people to be honest about what is actually broken.We use exactly this approach with boards and executive teams. When we run it for clients, we design the workshop, facilitate the session, and then turn the output into a prioritised, risk-aware delivery roadmap.

If you get to the end and realise you’d rather have a neutral facilitator in the room, that’s what we’re here for. Even if you do bring in external help, understanding the framework first means you’ll get far more value from the time you spend together.

2. Introducing the Strategy Canvas

The Strategy Canvas is a planning tool that forces you to work backwards from your goal. Most organisations do this the wrong way round. They pick technology, then work out what to do with it. This canvas makes you start with where you want to get to. Only then do you figure out what you need to do, what resources you need, and what has to change about how people actually work.

Click Here: It is available here on the Miroverse.

Why a canvas? Why a workshop?

Strategy doesn't happen in isolation. It happens through conversation, debate, and honest assessment of what's actually possible. A strategy document written by one person and presented to leadership rarely survives contact with reality. It gets nodded at, filed, and forgotten.

A workshop forces the conversation to happen. It gets decision-makers in a room together, looking at the same information, making trade-offs in real time. The canvas gives structure to that conversation so it doesn't devolve into unfocused debate about everything at once.

The visual nature matters. Post-it notes on a wall (or a Miro board) let everyone see the whole picture simultaneously. You can spot gaps, dependencies, and contradictions that aren't obvious in a written document. When someone says "we need better data" and you look at the canvas and see they haven't identified who will clean that data or how people will be trained to use it, the gap becomes obvious.

How this works in practice

When we run this for clients, we don't just turn up with a blank canvas and hope for the best. We recommend spending a few days beforehand understanding the business. Talk to people individually - leadership, technical staff, whoever will be involved in executing whatever comes out of the workshop. Ask about previous initiatives that failed and why. Look at what's already been tried. Identify the political dynamics and sacred cows.

This pre-work serves two purposes. First, it means the workshop is productive from minute one because you're not spending the first hour just establishing context. Second, you spot the gaps between what people say publicly and what they say privately. That tells you where the difficult conversations need to happen.

The workshop itself is where the canvas gets filled out. A good facilitator will push for specificity and make sure the uncomfortable topics don't get sidestepped. Afterwards, spend a couple of days producing a clear deliverable - the completed canvas, a prioritised action plan, and an honest assessment of what the real blockers are.

If you're running this internally, the same principles apply. Do the pre-work. Make sure you have the right people in the room. Don't rush the process. And be prepared for the conversation to get uncomfortable - that's usually a sign it's working.

What the canvas looks like

The canvas is a single page divided into four columns that move from right to left. On the right: your goal, written on a green post-it note. Moving left, three columns: what to do (yellow notes), what you need (blue notes), and ways of working (pink notes). Each column asks a specific question and forces specific thinking.

It covers four areas of any business:

Client Value (how you create value for clients)

Risk (how you manage compliance, controls, and regulation)

Teams (your people and their capabilities)

Operations (how you deliver efficiently)

Every action, every resource requirement, and every cultural change maps to one of these four areas. This structure stops you missing critical pieces. You might remember to think about operations but forget about risk. You might focus on client value but ignore team capabilities. The four areas make sure you think through the whole business.

The canvas uses coloured post-it notes to distinguish between different types of thinking. Green for your goal. Yellow for actions. Blue for resources. Pink for behaviour and culture changes. This visual system keeps conversations focused and stops people jumping between "what we want to achieve" and "what tools we should buy" as if they are the same question.

Once you've filled the canvas with post-its, you add dots and arrows. Red dots mark gaps or blockers. Green dots mark quick wins. Orange dots show dependencies - where one thing must happen before another. Stars indicate critical success factors. Arrows between orange dots show the sequence. This layer turns the canvas from a list of ideas into a prioritised plan.

You can use this for enterprise-wide transformation or a single department initiative. The scale changes but the logic stays the same. Define what winning looks like, work backwards to what needs to happen, be honest about what has to change.

Using this guide

This guide gives you everything you need to run this yourself. The framework is simple; the hard part is getting senior people to be honest about what is actually broken.We use exactly this approach with boards and executive teams. When we run it for clients, we design the workshop, facilitate the session, and then turn the output into a prioritised, risk-aware delivery roadmap.

If you get to the end and realise you’d rather have a neutral facilitator in the room, that’s what we’re here for. Even if you do bring in external help, understanding the framework first means you’ll get far more value from the time you spend together.

2. Introducing the Strategy Canvas

The Strategy Canvas is a planning tool that forces you to work backwards from your goal. Most organisations do this the wrong way round. They pick technology, then work out what to do with it. This canvas makes you start with where you want to get to. Only then do you figure out what you need to do, what resources you need, and what has to change about how people actually work.

Click Here: It is available here on the Miroverse.

Why a canvas? Why a workshop?

Strategy doesn't happen in isolation. It happens through conversation, debate, and honest assessment of what's actually possible. A strategy document written by one person and presented to leadership rarely survives contact with reality. It gets nodded at, filed, and forgotten.

A workshop forces the conversation to happen. It gets decision-makers in a room together, looking at the same information, making trade-offs in real time. The canvas gives structure to that conversation so it doesn't devolve into unfocused debate about everything at once.

The visual nature matters. Post-it notes on a wall (or a Miro board) let everyone see the whole picture simultaneously. You can spot gaps, dependencies, and contradictions that aren't obvious in a written document. When someone says "we need better data" and you look at the canvas and see they haven't identified who will clean that data or how people will be trained to use it, the gap becomes obvious.

How this works in practice

When we run this for clients, we don't just turn up with a blank canvas and hope for the best. We recommend spending a few days beforehand understanding the business. Talk to people individually - leadership, technical staff, whoever will be involved in executing whatever comes out of the workshop. Ask about previous initiatives that failed and why. Look at what's already been tried. Identify the political dynamics and sacred cows.

This pre-work serves two purposes. First, it means the workshop is productive from minute one because you're not spending the first hour just establishing context. Second, you spot the gaps between what people say publicly and what they say privately. That tells you where the difficult conversations need to happen.

The workshop itself is where the canvas gets filled out. A good facilitator will push for specificity and make sure the uncomfortable topics don't get sidestepped. Afterwards, spend a couple of days producing a clear deliverable - the completed canvas, a prioritised action plan, and an honest assessment of what the real blockers are.

If you're running this internally, the same principles apply. Do the pre-work. Make sure you have the right people in the room. Don't rush the process. And be prepared for the conversation to get uncomfortable - that's usually a sign it's working.

What the canvas looks like

The canvas is a single page divided into four columns that move from right to left. On the right: your goal, written on a green post-it note. Moving left, three columns: what to do (yellow notes), what you need (blue notes), and ways of working (pink notes). Each column asks a specific question and forces specific thinking.

It covers four areas of any business:

Client Value (how you create value for clients)

Risk (how you manage compliance, controls, and regulation)

Teams (your people and their capabilities)

Operations (how you deliver efficiently)

Every action, every resource requirement, and every cultural change maps to one of these four areas. This structure stops you missing critical pieces. You might remember to think about operations but forget about risk. You might focus on client value but ignore team capabilities. The four areas make sure you think through the whole business.

The canvas uses coloured post-it notes to distinguish between different types of thinking. Green for your goal. Yellow for actions. Blue for resources. Pink for behaviour and culture changes. This visual system keeps conversations focused and stops people jumping between "what we want to achieve" and "what tools we should buy" as if they are the same question.

Once you've filled the canvas with post-its, you add dots and arrows. Red dots mark gaps or blockers. Green dots mark quick wins. Orange dots show dependencies - where one thing must happen before another. Stars indicate critical success factors. Arrows between orange dots show the sequence. This layer turns the canvas from a list of ideas into a prioritised plan.

You can use this for enterprise-wide transformation or a single department initiative. The scale changes but the logic stays the same. Define what winning looks like, work backwards to what needs to happen, be honest about what has to change.

Using this guide

This guide gives you everything you need to run this yourself. The framework is simple; the hard part is getting senior people to be honest about what is actually broken.We use exactly this approach with boards and executive teams. When we run it for clients, we design the workshop, facilitate the session, and then turn the output into a prioritised, risk-aware delivery roadmap.

If you get to the end and realise you’d rather have a neutral facilitator in the room, that’s what we’re here for. Even if you do bring in external help, understanding the framework first means you’ll get far more value from the time you spend together.

3. Before You Start

Whether you're facilitating this internally or bringing in external help, you need the right people in the room. This is not a working group exercise you delegate to middle management. You need the people who can actually make decisions and commit budget. If the conversation keeps ending with "we will need to check with..." then you have the wrong people.

Typical participants include the CEO or managing director, CFO, heads of major functions or business units, and anyone who controls significant budget or resources. You do not need everyone, but you need anyone whose support you cannot do without.

Think about who is responsible for executing changes and who is accountable for outcomes. Those people must be in the room. If your strategy requires the operations director to change how their team works, they need to be there. If it requires the IT director to build or integrate systems, they need to be there. If it requires budget approval from the CFO, they need to be there.

You may also need people who should be consulted because they have critical knowledge or relationships, even if they are not directly responsible for execution. A senior client partner who understands what clients actually value. A technical lead who knows what is realistic and what is fantasy. Someone who has tried this before and knows where it went wrong.

You do not need people who just need to be kept informed. They can be briefed after the workshop. Including them dilutes the conversation and slows decision-making. If someone's main contribution would be "can you send me the notes afterwards?" they should not be in the workshop.

The worst outcome is running a great workshop, producing a clear plan, and then discovering that someone not in the room has veto power and disagrees with the goal. Know who your decision-makers are before you start.

Set aside half a day minimum, ideally a full day. This is not something you squeeze into a two-hour slot between other meetings. People need time to think, debate, and get uncomfortable. If you rush it, you get superficial answers.

Physical space works better than virtual if you can manage it. There is something about standing around a wall of post-it notes that creates better conversations than staring at a Miro board on a screen. But virtual can work if your team is distributed. Just make sure everyone can see the canvas and contribute easily.

You will need post-it notes in four colours (green, yellow, blue, pink), markers, and space on a wall or large whiteboard. If you are doing this virtually, set up a Miro board with the canvas template. Either way, make sure everyone understands the colour system before you start.

Do some pre-work. This does not mean producing a draft strategy and presenting it for approval. That defeats the point. But you should understand the context. Talk to participants individually beforehand. What do they think the goal should be? Where do they see gaps or blockers? What initiatives have failed before and why?

This pre-work serves two purposes. First, you avoid spending the first hour of the workshop just getting everyone aligned on basic context. Second, you spot the political dynamics. If three people tell you individually that the real problem is the sales director's refusal to use the CRM, but nobody says this in group settings, you know you have a facilitation challenge.

Be clear about what this session will produce. You are not walking out with a detailed implementation plan. You are walking out with clarity on the goal, the major actions required across four business areas, the resources you need, and the culture changes that have to happen. That is the foundation. The detailed project plan comes after.

3. Before You Start

Whether you're facilitating this internally or bringing in external help, you need the right people in the room. This is not a working group exercise you delegate to middle management. You need the people who can actually make decisions and commit budget. If the conversation keeps ending with "we will need to check with..." then you have the wrong people.

Typical participants include the CEO or managing director, CFO, heads of major functions or business units, and anyone who controls significant budget or resources. You do not need everyone, but you need anyone whose support you cannot do without.

Think about who is responsible for executing changes and who is accountable for outcomes. Those people must be in the room. If your strategy requires the operations director to change how their team works, they need to be there. If it requires the IT director to build or integrate systems, they need to be there. If it requires budget approval from the CFO, they need to be there.

You may also need people who should be consulted because they have critical knowledge or relationships, even if they are not directly responsible for execution. A senior client partner who understands what clients actually value. A technical lead who knows what is realistic and what is fantasy. Someone who has tried this before and knows where it went wrong.

You do not need people who just need to be kept informed. They can be briefed after the workshop. Including them dilutes the conversation and slows decision-making. If someone's main contribution would be "can you send me the notes afterwards?" they should not be in the workshop.

The worst outcome is running a great workshop, producing a clear plan, and then discovering that someone not in the room has veto power and disagrees with the goal. Know who your decision-makers are before you start.

Set aside half a day minimum, ideally a full day. This is not something you squeeze into a two-hour slot between other meetings. People need time to think, debate, and get uncomfortable. If you rush it, you get superficial answers.

Physical space works better than virtual if you can manage it. There is something about standing around a wall of post-it notes that creates better conversations than staring at a Miro board on a screen. But virtual can work if your team is distributed. Just make sure everyone can see the canvas and contribute easily.

You will need post-it notes in four colours (green, yellow, blue, pink), markers, and space on a wall or large whiteboard. If you are doing this virtually, set up a Miro board with the canvas template. Either way, make sure everyone understands the colour system before you start.

Do some pre-work. This does not mean producing a draft strategy and presenting it for approval. That defeats the point. But you should understand the context. Talk to participants individually beforehand. What do they think the goal should be? Where do they see gaps or blockers? What initiatives have failed before and why?

This pre-work serves two purposes. First, you avoid spending the first hour of the workshop just getting everyone aligned on basic context. Second, you spot the political dynamics. If three people tell you individually that the real problem is the sales director's refusal to use the CRM, but nobody says this in group settings, you know you have a facilitation challenge.

Be clear about what this session will produce. You are not walking out with a detailed implementation plan. You are walking out with clarity on the goal, the major actions required across four business areas, the resources you need, and the culture changes that have to happen. That is the foundation. The detailed project plan comes after.

3. Before You Start

Whether you're facilitating this internally or bringing in external help, you need the right people in the room. This is not a working group exercise you delegate to middle management. You need the people who can actually make decisions and commit budget. If the conversation keeps ending with "we will need to check with..." then you have the wrong people.

Typical participants include the CEO or managing director, CFO, heads of major functions or business units, and anyone who controls significant budget or resources. You do not need everyone, but you need anyone whose support you cannot do without.

Think about who is responsible for executing changes and who is accountable for outcomes. Those people must be in the room. If your strategy requires the operations director to change how their team works, they need to be there. If it requires the IT director to build or integrate systems, they need to be there. If it requires budget approval from the CFO, they need to be there.

You may also need people who should be consulted because they have critical knowledge or relationships, even if they are not directly responsible for execution. A senior client partner who understands what clients actually value. A technical lead who knows what is realistic and what is fantasy. Someone who has tried this before and knows where it went wrong.

You do not need people who just need to be kept informed. They can be briefed after the workshop. Including them dilutes the conversation and slows decision-making. If someone's main contribution would be "can you send me the notes afterwards?" they should not be in the workshop.

The worst outcome is running a great workshop, producing a clear plan, and then discovering that someone not in the room has veto power and disagrees with the goal. Know who your decision-makers are before you start.

Set aside half a day minimum, ideally a full day. This is not something you squeeze into a two-hour slot between other meetings. People need time to think, debate, and get uncomfortable. If you rush it, you get superficial answers.

Physical space works better than virtual if you can manage it. There is something about standing around a wall of post-it notes that creates better conversations than staring at a Miro board on a screen. But virtual can work if your team is distributed. Just make sure everyone can see the canvas and contribute easily.

You will need post-it notes in four colours (green, yellow, blue, pink), markers, and space on a wall or large whiteboard. If you are doing this virtually, set up a Miro board with the canvas template. Either way, make sure everyone understands the colour system before you start.

Do some pre-work. This does not mean producing a draft strategy and presenting it for approval. That defeats the point. But you should understand the context. Talk to participants individually beforehand. What do they think the goal should be? Where do they see gaps or blockers? What initiatives have failed before and why?

This pre-work serves two purposes. First, you avoid spending the first hour of the workshop just getting everyone aligned on basic context. Second, you spot the political dynamics. If three people tell you individually that the real problem is the sales director's refusal to use the CRM, but nobody says this in group settings, you know you have a facilitation challenge.

Be clear about what this session will produce. You are not walking out with a detailed implementation plan. You are walking out with clarity on the goal, the major actions required across four business areas, the resources you need, and the culture changes that have to happen. That is the foundation. The detailed project plan comes after.

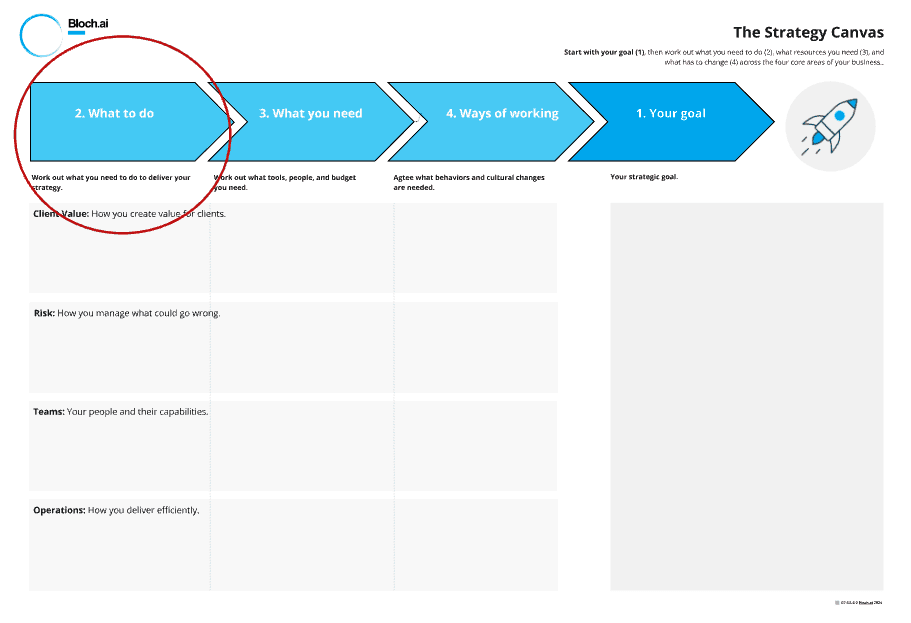

4. How To Use The Canvas

The canvas works right to left, even though that feels counter-intuitive. Look at the blank template below. You start with your goal on the right-hand side, in the section marked "1. Your goal". Everything else flows backwards from there.

Start with your goal (Green post-its)

Write your goal on a green post-it in the right-hand column. This needs to be specific and measurable. Not "improve customer service" but "reduce average resolution time from 48 hours to 4 hours." Not "increase revenue" but "grow revenue from mid-market clients by 30% within 18 months."

Let's use a realistic example: a professional services firm that wants to use AI but hasn't figured out what for. After discussion, they define their goal:

Goal (Green): "Reduce proposal response time from 3 weeks to 5 days while maintaining win rate above 30%"

This is specific and measurable. They currently take three weeks to respond to RFPs. Competitors are faster. They are losing opportunities because by the time they respond, prospects have moved on. But they cannot sacrifice quality - their 30% win rate on submitted proposals is good, and they need to maintain it.

Notice this goal says nothing about AI or chatbots yet. It starts with the business outcome. Only through working backwards will they discover what they actually need.

Compare that to where they started: "We need an AI strategy." That is not a goal. Or "We should implement GPT for proposals." That is a solution looking for a problem. By forcing them to articulate the actual business goal first, the canvas ensures any AI implementation serves a real purpose.

The goal needs to be ambitious enough to matter but realistic enough to be credible. If everyone in the room knows it's impossible, they will not engage. If it's too easy, you will not uncover the real barriers.

You may have multiple goals if they are tightly related. But be careful. Three unrelated goals that require completely different actions means you are spreading yourself thin. Better to pick one, do it properly, then move to the next.

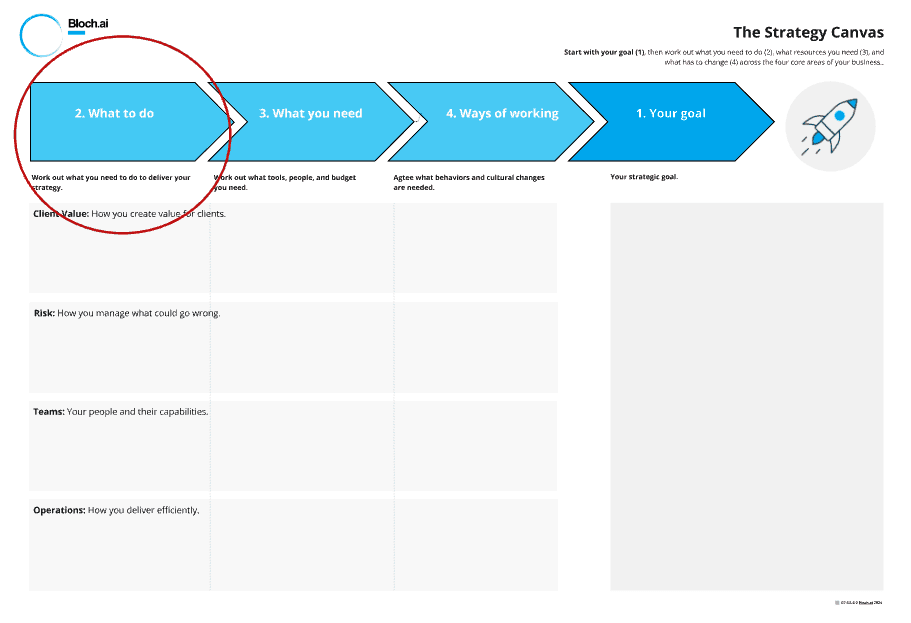

Work out what you need to do (Yellow post-its)

Once you have the goal, move left to the "2. What to do" column. This is where you map the actions required to achieve your goal. For each of the four business areas (Client Value, Risk, Teams, Operations), write yellow post-its describing specific actions.

For our professional services firm trying to speed up proposals, the actions might look like this:

Client Value:

Build searchable proposal library with past winning proposals

Enable clients to ask questions during bid process via AI chat

Risk:

Automate conflicts checking against client and matter database

Deploy AI scanning for regulatory requirements in RFP documents

Build automated compliance checklist generation for each proposal type

Teams:

Train bid team (8 people) on prompt engineering for proposals

Up-skill junior staff on proposal best practices using AI assistance

Operations:

Deploy secure AI chat system for proposal drafting

Build AI agents for automated research and section generation

Integrate with existing document management system

Each of these is a concrete action. Not "use AI for proposals" but specific things that will happen. Some are broad (build AI agents) and will need breaking down into sub-tasks later, but they are specific enough to understand what success looks like.

Notice how "deploy secure AI chat system" and "build AI agents" have emerged as actions - but only after defining the goal and thinking through what needs to happen. They didn't start by saying "we need chatbots." They started with "we need faster proposals" and discovered that chatbots and agents are part of the solution.

Be specific about what will actually be different. Not "implement AI" but "deploy secure AI chat system on our Azure tenant for proposal drafting, with access to historical proposal library." Not "train people" but "run 4-hour workshop on prompt engineering for proposal writing, covering research, section drafting, and quality review, for all 8 bid team members."

This is where you break down the big goal into concrete actions. If you cannot describe what people will actually be doing differently, you do not have an action, you have an aspiration.

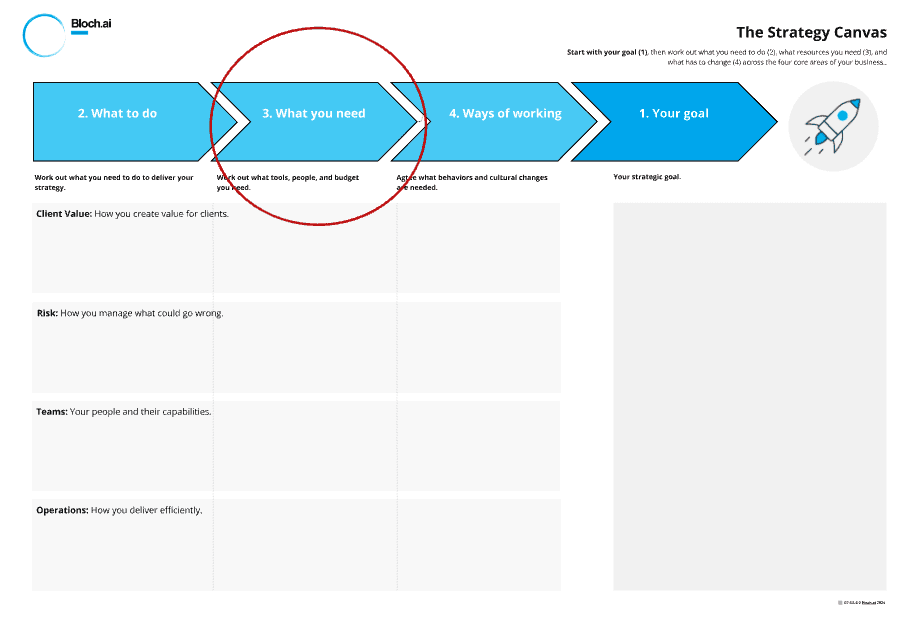

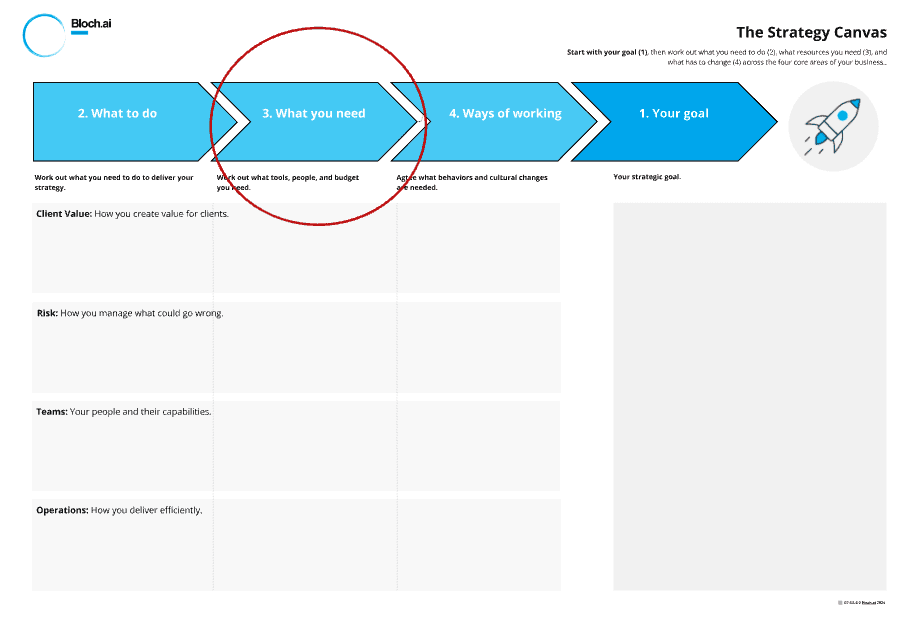

Identify what you need (Blue post-its)

Move left again to "3. What you need". For each action, write blue post-its describing the resources required. This includes tools, people, budget, data, and time.

For our proposal example:

Client Value:

Historical proposal database (past 3 years, 200+ proposals)

Win/loss analysis data to identify what makes proposals succeed

Client feedback on current proposal quality

Risk:

Conflicts database in searchable format (currently spreadsheet)

Regulatory requirements library covering key sectors

Compliance team input on checklist requirements (2 days)

Teams:

Training budget: £5k for external facilitation + staff time (32 hours)

Access to proposal best practices library

Ongoing coaching for first month

Operations:

Enterprise AI platform (Azure OpenAI Service): £500/month

GPT-4 API access: estimated 2M tokens/month at £40/month

Integration developer: 3 weeks at £1,200/day = £18k

Document management system API documentation

Again, wherever possible be specific. If you can, not "AI tools" but "Azure OpenAI Service with GPT-5" Not "someone to build it" but "integration developer with experience in Azure OpenAI and DMS APIs, 3-week engagement, approximately £18k." Get as far as you can in the session, it could be that you do not know what you need but get as many requirements as possible.

If you do not know exact costs, that's fine, but you should know order of magnitude. The firm can now see this is roughly a £25-30k investment to get started, plus £500-600/month ongoing. That helps them decide whether the goal (faster proposals, potentially more wins) justifies the investment.

This column also surfaces resource gaps. They need historical proposals in a usable format - do they have that? They need their document management system to have API access - does it? If not, that is a blocker that needs addressing first.

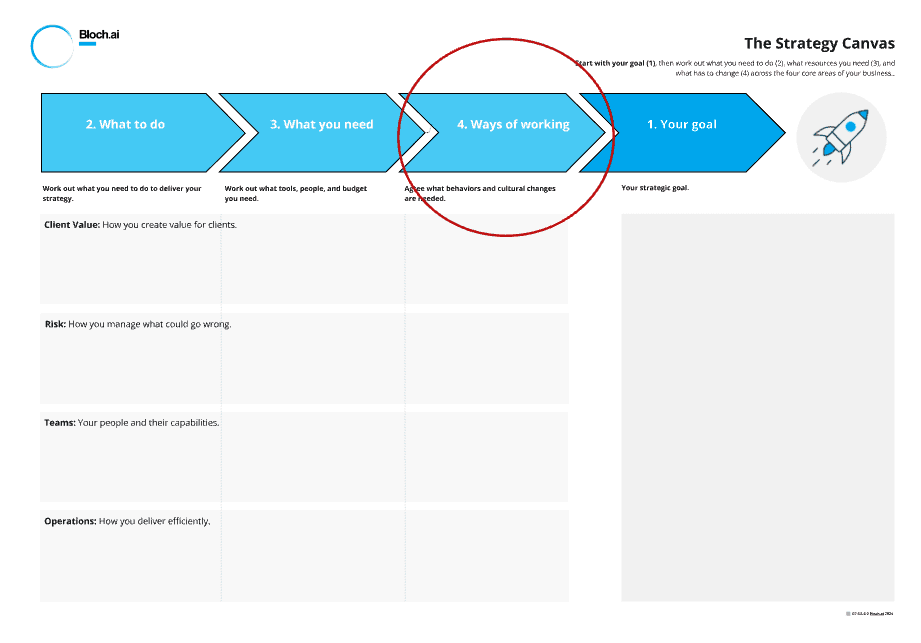

Agree what has to change (Pink post-its)

This is the uncomfortable bit. Move left again to "4. Ways of working". For each action, write pink post-its describing the behaviour and culture changes required.

For our proposal example:

Client Value:

Partners must contribute winning proposals to shared library (currently hoarded)

Accept AI-drafted sections with human review rather than writing everything from scratch

Respond to client questions within 24 hours during bid process

Risk:

Compliance team trusts AI-flagged conflicts with spot-check verification, not manual review of every matter

Accept AI-generated checklists as starting point rather than building from scratch each time

Risk sign-off moves from gatekeeper at end to advisor throughout process

Teams:

Junior staff empowered to draft proposal sections using AI assistance

Partners shift from writing to reviewing and enhancing

Accept that proposal quality comes from good prompts + good review, not from writing everything yourself

Operations:

Use templates and AI assistance as starting point, not bypass for thinking

Measure and report on proposal response times weekly

Commit to 5-day maximum turnaround with no exceptions

These are behaviour changes, not aspirations. "Partners must contribute winning proposals to shared library" is brutally honest. It names the problem: partners currently hoard their best work because they see it as competitive advantage internally. That needs to stop.

"Accept AI-drafted sections with human review" is a significant culture shift. It means trusting that AI plus review can be as good as writing from scratch. For professional services firms where writing skill is core identity, that is uncomfortable.

"Junior staff empowered to draft proposal sections" flips the current model where juniors do research and partners write. Now juniors can draft using AI, and partners review and enhance. That requires partners to trust junior judgement and junior staff to step up.

This is not about tools or processes. This is about how people actually work. If your goal requires partners to share their best work and they currently protect it, that is a culture change. If it requires people to trust AI output with verification rather than doing everything manually, that is a culture change.

Most people want to skip this column because it is awkward. Do not skip it. This is where most strategies fail. You can buy tools, you can hire people, but changing how people work takes time, effort, and political capital.

Be honest here. If the real blocker is that the senior partner refuses to use templates because he believes every client is unique, write that down. If the issue is that junior staff are not trusted to draft client-facing content, write that down. The whole point of this exercise is to surface the real barriers, not produce a sanitised version that sounds good in board papers.

Add priority and dependency markers

Once you have filled the canvas with post-its, step back and add dots and arrows to show priority, status, and dependencies.

The key shows you what each marking means:

Red dot: Gap or blocker that needs addressing

Green dot: Quick win that can be delivered fast

Orange dot: Dependency on another item

Star: High priority or critical success factor

Arrows between orange dots: Show which items must happen first

For the proposal example, you might mark:

Red dot on "Partners must contribute winning proposals to shared library" - this is a known blocker, partners are resistant

Green dot on "Train bid team on prompt engineering" - can be done quickly, builds capability for everything else

Orange dot on "Deploy secure AI chat system" with arrow from "Secure Azure deployment within firm's tenant" - can't deploy until security is approved

Star on "Reduce proposal response time from 3 weeks to 5 days" goal and on "Deploy secure AI chat system" - these are critical to success

Red dots force you to be honest about what is stopping you. The partner resistance to sharing proposals is real. It needs addressing through leadership intervention, incentive changes, or both. Ignoring it means the proposal library will be empty and the AI will have nothing to learn from.

Green dots identify momentum-builders. Training the bid team is quick, relatively cheap, and builds confidence that this can work. It also starts changing the culture before the technology is fully deployed.

Orange dots and arrows show the critical path. You cannot deploy the AI system until information security approves it. So security approval is on the critical path. If that takes three months, everything else waits. Better to know that now.

Stars mark what absolutely must happen. You should not have many stars. If everything is critical, nothing is critical. Three to five starred items across the whole canvas is plenty.

4. How To Use The Canvas

The canvas works right to left, even though that feels counter-intuitive. Look at the blank template below. You start with your goal on the right-hand side, in the section marked "1. Your goal". Everything else flows backwards from there.

Start with your goal (Green post-its)

Write your goal on a green post-it in the right-hand column. This needs to be specific and measurable. Not "improve customer service" but "reduce average resolution time from 48 hours to 4 hours." Not "increase revenue" but "grow revenue from mid-market clients by 30% within 18 months."

Let's use a realistic example: a professional services firm that wants to use AI but hasn't figured out what for. After discussion, they define their goal:

Goal (Green): "Reduce proposal response time from 3 weeks to 5 days while maintaining win rate above 30%"

This is specific and measurable. They currently take three weeks to respond to RFPs. Competitors are faster. They are losing opportunities because by the time they respond, prospects have moved on. But they cannot sacrifice quality - their 30% win rate on submitted proposals is good, and they need to maintain it.

Notice this goal says nothing about AI or chatbots yet. It starts with the business outcome. Only through working backwards will they discover what they actually need.

Compare that to where they started: "We need an AI strategy." That is not a goal. Or "We should implement GPT for proposals." That is a solution looking for a problem. By forcing them to articulate the actual business goal first, the canvas ensures any AI implementation serves a real purpose.

The goal needs to be ambitious enough to matter but realistic enough to be credible. If everyone in the room knows it's impossible, they will not engage. If it's too easy, you will not uncover the real barriers.

You may have multiple goals if they are tightly related. But be careful. Three unrelated goals that require completely different actions means you are spreading yourself thin. Better to pick one, do it properly, then move to the next.

Work out what you need to do (Yellow post-its)

Once you have the goal, move left to the "2. What to do" column. This is where you map the actions required to achieve your goal. For each of the four business areas (Client Value, Risk, Teams, Operations), write yellow post-its describing specific actions.

For our professional services firm trying to speed up proposals, the actions might look like this:

Client Value:

Build searchable proposal library with past winning proposals

Enable clients to ask questions during bid process via AI chat

Risk:

Automate conflicts checking against client and matter database

Deploy AI scanning for regulatory requirements in RFP documents

Build automated compliance checklist generation for each proposal type

Teams:

Train bid team (8 people) on prompt engineering for proposals

Up-skill junior staff on proposal best practices using AI assistance

Operations:

Deploy secure AI chat system for proposal drafting

Build AI agents for automated research and section generation

Integrate with existing document management system

Each of these is a concrete action. Not "use AI for proposals" but specific things that will happen. Some are broad (build AI agents) and will need breaking down into sub-tasks later, but they are specific enough to understand what success looks like.

Notice how "deploy secure AI chat system" and "build AI agents" have emerged as actions - but only after defining the goal and thinking through what needs to happen. They didn't start by saying "we need chatbots." They started with "we need faster proposals" and discovered that chatbots and agents are part of the solution.

Be specific about what will actually be different. Not "implement AI" but "deploy secure AI chat system on our Azure tenant for proposal drafting, with access to historical proposal library." Not "train people" but "run 4-hour workshop on prompt engineering for proposal writing, covering research, section drafting, and quality review, for all 8 bid team members."

This is where you break down the big goal into concrete actions. If you cannot describe what people will actually be doing differently, you do not have an action, you have an aspiration.

Identify what you need (Blue post-its)

Move left again to "3. What you need". For each action, write blue post-its describing the resources required. This includes tools, people, budget, data, and time.

For our proposal example:

Client Value:

Historical proposal database (past 3 years, 200+ proposals)

Win/loss analysis data to identify what makes proposals succeed

Client feedback on current proposal quality

Risk:

Conflicts database in searchable format (currently spreadsheet)

Regulatory requirements library covering key sectors

Compliance team input on checklist requirements (2 days)

Teams:

Training budget: £5k for external facilitation + staff time (32 hours)

Access to proposal best practices library

Ongoing coaching for first month

Operations:

Enterprise AI platform (Azure OpenAI Service): £500/month

GPT-4 API access: estimated 2M tokens/month at £40/month

Integration developer: 3 weeks at £1,200/day = £18k

Document management system API documentation

Again, wherever possible be specific. If you can, not "AI tools" but "Azure OpenAI Service with GPT-5" Not "someone to build it" but "integration developer with experience in Azure OpenAI and DMS APIs, 3-week engagement, approximately £18k." Get as far as you can in the session, it could be that you do not know what you need but get as many requirements as possible.

If you do not know exact costs, that's fine, but you should know order of magnitude. The firm can now see this is roughly a £25-30k investment to get started, plus £500-600/month ongoing. That helps them decide whether the goal (faster proposals, potentially more wins) justifies the investment.

This column also surfaces resource gaps. They need historical proposals in a usable format - do they have that? They need their document management system to have API access - does it? If not, that is a blocker that needs addressing first.

Agree what has to change (Pink post-its)

This is the uncomfortable bit. Move left again to "4. Ways of working". For each action, write pink post-its describing the behaviour and culture changes required.

For our proposal example:

Client Value:

Partners must contribute winning proposals to shared library (currently hoarded)

Accept AI-drafted sections with human review rather than writing everything from scratch

Respond to client questions within 24 hours during bid process

Risk:

Compliance team trusts AI-flagged conflicts with spot-check verification, not manual review of every matter

Accept AI-generated checklists as starting point rather than building from scratch each time

Risk sign-off moves from gatekeeper at end to advisor throughout process

Teams:

Junior staff empowered to draft proposal sections using AI assistance

Partners shift from writing to reviewing and enhancing

Accept that proposal quality comes from good prompts + good review, not from writing everything yourself

Operations:

Use templates and AI assistance as starting point, not bypass for thinking

Measure and report on proposal response times weekly

Commit to 5-day maximum turnaround with no exceptions

These are behaviour changes, not aspirations. "Partners must contribute winning proposals to shared library" is brutally honest. It names the problem: partners currently hoard their best work because they see it as competitive advantage internally. That needs to stop.

"Accept AI-drafted sections with human review" is a significant culture shift. It means trusting that AI plus review can be as good as writing from scratch. For professional services firms where writing skill is core identity, that is uncomfortable.

"Junior staff empowered to draft proposal sections" flips the current model where juniors do research and partners write. Now juniors can draft using AI, and partners review and enhance. That requires partners to trust junior judgement and junior staff to step up.

This is not about tools or processes. This is about how people actually work. If your goal requires partners to share their best work and they currently protect it, that is a culture change. If it requires people to trust AI output with verification rather than doing everything manually, that is a culture change.

Most people want to skip this column because it is awkward. Do not skip it. This is where most strategies fail. You can buy tools, you can hire people, but changing how people work takes time, effort, and political capital.

Be honest here. If the real blocker is that the senior partner refuses to use templates because he believes every client is unique, write that down. If the issue is that junior staff are not trusted to draft client-facing content, write that down. The whole point of this exercise is to surface the real barriers, not produce a sanitised version that sounds good in board papers.

Add priority and dependency markers

Once you have filled the canvas with post-its, step back and add dots and arrows to show priority, status, and dependencies.

The key shows you what each marking means:

Red dot: Gap or blocker that needs addressing

Green dot: Quick win that can be delivered fast

Orange dot: Dependency on another item

Star: High priority or critical success factor

Arrows between orange dots: Show which items must happen first

For the proposal example, you might mark:

Red dot on "Partners must contribute winning proposals to shared library" - this is a known blocker, partners are resistant

Green dot on "Train bid team on prompt engineering" - can be done quickly, builds capability for everything else

Orange dot on "Deploy secure AI chat system" with arrow from "Secure Azure deployment within firm's tenant" - can't deploy until security is approved

Star on "Reduce proposal response time from 3 weeks to 5 days" goal and on "Deploy secure AI chat system" - these are critical to success

Red dots force you to be honest about what is stopping you. The partner resistance to sharing proposals is real. It needs addressing through leadership intervention, incentive changes, or both. Ignoring it means the proposal library will be empty and the AI will have nothing to learn from.

Green dots identify momentum-builders. Training the bid team is quick, relatively cheap, and builds confidence that this can work. It also starts changing the culture before the technology is fully deployed.

Orange dots and arrows show the critical path. You cannot deploy the AI system until information security approves it. So security approval is on the critical path. If that takes three months, everything else waits. Better to know that now.

Stars mark what absolutely must happen. You should not have many stars. If everything is critical, nothing is critical. Three to five starred items across the whole canvas is plenty.

4. How To Use The Canvas

The canvas works right to left, even though that feels counter-intuitive. Look at the blank template below. You start with your goal on the right-hand side, in the section marked "1. Your goal". Everything else flows backwards from there.

Start with your goal (Green post-its)

Write your goal on a green post-it in the right-hand column. This needs to be specific and measurable. Not "improve customer service" but "reduce average resolution time from 48 hours to 4 hours." Not "increase revenue" but "grow revenue from mid-market clients by 30% within 18 months."

Let's use a realistic example: a professional services firm that wants to use AI but hasn't figured out what for. After discussion, they define their goal:

Goal (Green): "Reduce proposal response time from 3 weeks to 5 days while maintaining win rate above 30%"

This is specific and measurable. They currently take three weeks to respond to RFPs. Competitors are faster. They are losing opportunities because by the time they respond, prospects have moved on. But they cannot sacrifice quality - their 30% win rate on submitted proposals is good, and they need to maintain it.

Notice this goal says nothing about AI or chatbots yet. It starts with the business outcome. Only through working backwards will they discover what they actually need.

Compare that to where they started: "We need an AI strategy." That is not a goal. Or "We should implement GPT for proposals." That is a solution looking for a problem. By forcing them to articulate the actual business goal first, the canvas ensures any AI implementation serves a real purpose.

The goal needs to be ambitious enough to matter but realistic enough to be credible. If everyone in the room knows it's impossible, they will not engage. If it's too easy, you will not uncover the real barriers.

You may have multiple goals if they are tightly related. But be careful. Three unrelated goals that require completely different actions means you are spreading yourself thin. Better to pick one, do it properly, then move to the next.

Work out what you need to do (Yellow post-its)

Once you have the goal, move left to the "2. What to do" column. This is where you map the actions required to achieve your goal. For each of the four business areas (Client Value, Risk, Teams, Operations), write yellow post-its describing specific actions.

For our professional services firm trying to speed up proposals, the actions might look like this:

Client Value:

Build searchable proposal library with past winning proposals

Enable clients to ask questions during bid process via AI chat

Risk:

Automate conflicts checking against client and matter database

Deploy AI scanning for regulatory requirements in RFP documents

Build automated compliance checklist generation for each proposal type

Teams:

Train bid team (8 people) on prompt engineering for proposals

Up-skill junior staff on proposal best practices using AI assistance

Operations:

Deploy secure AI chat system for proposal drafting

Build AI agents for automated research and section generation

Integrate with existing document management system

Each of these is a concrete action. Not "use AI for proposals" but specific things that will happen. Some are broad (build AI agents) and will need breaking down into sub-tasks later, but they are specific enough to understand what success looks like.

Notice how "deploy secure AI chat system" and "build AI agents" have emerged as actions - but only after defining the goal and thinking through what needs to happen. They didn't start by saying "we need chatbots." They started with "we need faster proposals" and discovered that chatbots and agents are part of the solution.

Be specific about what will actually be different. Not "implement AI" but "deploy secure AI chat system on our Azure tenant for proposal drafting, with access to historical proposal library." Not "train people" but "run 4-hour workshop on prompt engineering for proposal writing, covering research, section drafting, and quality review, for all 8 bid team members."

This is where you break down the big goal into concrete actions. If you cannot describe what people will actually be doing differently, you do not have an action, you have an aspiration.

Identify what you need (Blue post-its)

Move left again to "3. What you need". For each action, write blue post-its describing the resources required. This includes tools, people, budget, data, and time.

For our proposal example:

Client Value:

Historical proposal database (past 3 years, 200+ proposals)

Win/loss analysis data to identify what makes proposals succeed

Client feedback on current proposal quality

Risk:

Conflicts database in searchable format (currently spreadsheet)

Regulatory requirements library covering key sectors

Compliance team input on checklist requirements (2 days)

Teams:

Training budget: £5k for external facilitation + staff time (32 hours)

Access to proposal best practices library

Ongoing coaching for first month

Operations:

Enterprise AI platform (Azure OpenAI Service): £500/month

GPT-4 API access: estimated 2M tokens/month at £40/month

Integration developer: 3 weeks at £1,200/day = £18k

Document management system API documentation

Again, wherever possible be specific. If you can, not "AI tools" but "Azure OpenAI Service with GPT-5" Not "someone to build it" but "integration developer with experience in Azure OpenAI and DMS APIs, 3-week engagement, approximately £18k." Get as far as you can in the session, it could be that you do not know what you need but get as many requirements as possible.

If you do not know exact costs, that's fine, but you should know order of magnitude. The firm can now see this is roughly a £25-30k investment to get started, plus £500-600/month ongoing. That helps them decide whether the goal (faster proposals, potentially more wins) justifies the investment.

This column also surfaces resource gaps. They need historical proposals in a usable format - do they have that? They need their document management system to have API access - does it? If not, that is a blocker that needs addressing first.

Agree what has to change (Pink post-its)

This is the uncomfortable bit. Move left again to "4. Ways of working". For each action, write pink post-its describing the behaviour and culture changes required.

For our proposal example:

Client Value:

Partners must contribute winning proposals to shared library (currently hoarded)

Accept AI-drafted sections with human review rather than writing everything from scratch

Respond to client questions within 24 hours during bid process

Risk:

Compliance team trusts AI-flagged conflicts with spot-check verification, not manual review of every matter

Accept AI-generated checklists as starting point rather than building from scratch each time

Risk sign-off moves from gatekeeper at end to advisor throughout process

Teams:

Junior staff empowered to draft proposal sections using AI assistance

Partners shift from writing to reviewing and enhancing

Accept that proposal quality comes from good prompts + good review, not from writing everything yourself

Operations:

Use templates and AI assistance as starting point, not bypass for thinking

Measure and report on proposal response times weekly

Commit to 5-day maximum turnaround with no exceptions

These are behaviour changes, not aspirations. "Partners must contribute winning proposals to shared library" is brutally honest. It names the problem: partners currently hoard their best work because they see it as competitive advantage internally. That needs to stop.

"Accept AI-drafted sections with human review" is a significant culture shift. It means trusting that AI plus review can be as good as writing from scratch. For professional services firms where writing skill is core identity, that is uncomfortable.

"Junior staff empowered to draft proposal sections" flips the current model where juniors do research and partners write. Now juniors can draft using AI, and partners review and enhance. That requires partners to trust junior judgement and junior staff to step up.

This is not about tools or processes. This is about how people actually work. If your goal requires partners to share their best work and they currently protect it, that is a culture change. If it requires people to trust AI output with verification rather than doing everything manually, that is a culture change.

Most people want to skip this column because it is awkward. Do not skip it. This is where most strategies fail. You can buy tools, you can hire people, but changing how people work takes time, effort, and political capital.

Be honest here. If the real blocker is that the senior partner refuses to use templates because he believes every client is unique, write that down. If the issue is that junior staff are not trusted to draft client-facing content, write that down. The whole point of this exercise is to surface the real barriers, not produce a sanitised version that sounds good in board papers.

Add priority and dependency markers

Once you have filled the canvas with post-its, step back and add dots and arrows to show priority, status, and dependencies.

The key shows you what each marking means:

Red dot: Gap or blocker that needs addressing

Green dot: Quick win that can be delivered fast

Orange dot: Dependency on another item

Star: High priority or critical success factor

Arrows between orange dots: Show which items must happen first

For the proposal example, you might mark:

Red dot on "Partners must contribute winning proposals to shared library" - this is a known blocker, partners are resistant

Green dot on "Train bid team on prompt engineering" - can be done quickly, builds capability for everything else

Orange dot on "Deploy secure AI chat system" with arrow from "Secure Azure deployment within firm's tenant" - can't deploy until security is approved

Star on "Reduce proposal response time from 3 weeks to 5 days" goal and on "Deploy secure AI chat system" - these are critical to success

Red dots force you to be honest about what is stopping you. The partner resistance to sharing proposals is real. It needs addressing through leadership intervention, incentive changes, or both. Ignoring it means the proposal library will be empty and the AI will have nothing to learn from.

Green dots identify momentum-builders. Training the bid team is quick, relatively cheap, and builds confidence that this can work. It also starts changing the culture before the technology is fully deployed.

Orange dots and arrows show the critical path. You cannot deploy the AI system until information security approves it. So security approval is on the critical path. If that takes three months, everything else waits. Better to know that now.

Stars mark what absolutely must happen. You should not have many stars. If everything is critical, nothing is critical. Three to five starred items across the whole canvas is plenty.

5. The Four Strategic Dimensions

The canvas uses four perspectives to ensure you think through your strategy completely. These are not departments or org chart boxes. They are lenses through which to examine what needs to happen. Every action, resource requirement, and culture change should be considered through all four lenses.

Most strategies fail because they only think through one or two of these. You focus on operations (efficiency) but ignore client value (whether clients actually want faster service). You focus on teams (training) but ignore risk (whether your approach creates new liabilities). The canvas forces you to think through all four.

Client Value: How you create value for clients

This is about what your clients experience and why they choose you. Not what you think they value, what they actually value. Not what your marketing says you deliver, what you actually deliver.

In our proposal example, the firm initially thought this was purely about internal efficiency. Work through Client Value and they realised faster proposals are client value - prospects can make decisions faster. But more importantly, the ability to answer detailed questions during the bid process (via AI chat) is differentiating client value. Their competitors send static proposals and go silent for three weeks. They could provide dynamic responses within hours.

Common patterns here include automating routine interactions to free up expert time for complex client problems, using AI to generate insights that clients cannot get elsewhere, or compressing timelines from enquiry to delivery.

But here is where it gets uncomfortable. The culture changes in this area often expose that established processes serve internal convenience rather than client value.

Example: A law firm discovers that their 48-hour document turnaround time (which they are proud of) exists because partners review everything and partners are busy. Clients would pay more for 4-hour turnaround on urgent matters. But the culture of "everything must be partner-reviewed" prevents that. The client would be happy with senior associate review for urgent work, partner review for strategic decisions. But the firm's identity is wrapped up in "partner attention to every detail."

This example is a Client Value culture problem. The process serves partner control, not client needs. AI could enable senior associates to produce partner-quality work with AI assistance plus focused review. But only if partners accept that their value is strategic judgement, not personally touching every document.

Another pattern: firms assume clients want bespoke everything. Often clients want fast and good enough, not slow and perfect. But the firm's identity is "bespoke quality" so they over-deliver on a dimension clients do not value and under-deliver on speed, which clients do value. AI could help template the 80% that is commodity and reserve human expert time for the 20% that is genuinely bespoke. But the culture has to accept that "bespoke everything" is not always client value.

Risk: How you manage compliance, controls, and regulation

This is about how AI can make your risk and compliance functions faster, more thorough, and less of a bottleneck. Not risk as in "what might go wrong" but risk as a business function that needs to operate efficiently for you to hit your goals.

In our proposal example, the firm initially focused on the bid team. But proposals in professional services involve compliance work: conflicts checking, regulatory requirements, client due diligence, sector-specific constraints. If the bid team can turn proposals around in two days but compliance takes a week, you have not solved the problem.

Common patterns here include automating conflicts checks that currently require manual database searches, using AI to scan RFP documents and flag regulatory or contractual requirements, generating compliance checklists tailored to sector and client type, and accelerating due diligence by pulling together information from multiple sources.

Example: A law firm's conflicts checking takes 48 hours because someone manually searches three different systems and cross-references the results. AI could search all three simultaneously and flag potential conflicts in minutes. The compliance team then reviews the flags rather than doing the search themselves. Same rigour, fraction of the time.

Another pattern: firms treat compliance as a gate at the end of a process. Everything gets done, then compliance reviews it. If they find problems, work gets redone. AI enables a different model where compliance is embedded throughout. The proposal team gets real-time flags as they work: "this client has regulatory constraints in jurisdiction X" or "this matter type requires additional sign-off." Problems get caught early, not at the end.

The culture changes here are about the role of the risk function. Traditionally, risk and compliance teams add value by being thorough, which often means slow. Their identity is wrapped up in "we check everything carefully." Moving to "we design systems that check everything, and we verify the systems work" is a significant shift.

Example: A consulting firm's compliance team manually reviews every client contract before sign-off. They take pride in catching errors others miss. AI could flag unusual clauses and summarise key terms, with compliance reviewing the AI output and spot-checking the underlying documents. The team resists because it feels like they are being replaced. The culture change is helping them see that their value is judgement and expertise, not reading every word personally. AI handles volume; they handle exceptions and quality assurance.

Another pattern: risk teams as bottleneck versus risk teams as enabler. If your goal requires faster turnaround but risk sign-off takes a week because one person reviews everything, that person is on the critical path. The culture change might be delegating routine sign-offs to AI-assisted junior staff, with senior risk professionals focusing on complex or high-stakes matters. That requires the senior person to trust both the AI and their junior colleagues.

The culture change required is moving from "risk controls mean human review of everything" to "risk controls mean well-designed systems with appropriate human oversight." That sounds like less rigour. Done properly, it is more rigour because AI does not get tired, does not skip steps when busy, and does not miss things because it is Friday afternoon.

Teams: Your people and their capabilities

This is about whether you have the right people with the right skills to execute your strategy. Not whether you have people. Whether you have people who can actually do what needs doing.

The common mistake is assuming people will figure out new tools themselves. They will not. Or they will figure out bad habits that are hard to undo later.

In our proposal example, prompt engineering for proposals is a genuine skill. It is not "typing questions into ChatGPT." It is understanding how to structure a prompt so the AI accesses the right context, generates appropriate tone, and produces output that is useful not generic. That takes training and practice.

But the deeper issue is role change. Junior staff are being asked to draft sections they previously only researched. That is a step up in responsibility. Do they have the judgement to know when AI output is good enough and when it is wrong? Do they have the confidence to send a draft to a partner? Those are capability and culture questions.

Meanwhile, partners are being asked to shift from writing to reviewing and enhancing. That is a different skill. Some partners will resist because they define themselves as "writers" not "editors." Some will embrace it because they get more time for strategic thinking. You need to identify who is in which camp and manage accordingly.

Example: An accounting firm trains everyone on AI for financial analysis. Three months later, only 20% are using it regularly. Why? The training covered features ("here is how you upload data") but not judgement ("here is when AI analysis is trustworthy and when you need to verify"). People do not trust the output so they fall back to doing it manually. The missing piece was not tool training, it was building judgement.

Another pattern: firms hire "AI experts" without thinking about where they sit in the organization. You hire a data scientist. Where do they report? If they report to IT, they build technically impressive things that nobody uses because they are not connected to client delivery. If they report to a practice area, they build useful things for that practice but knowledge does not spread. You need to think about how expertise flows through the organization, not just whether you have expertise somewhere.

The culture change required is psychological safety. In professional services, there is immense pressure to appear competent at all times. Admitting "I do not understand how this works" or "I tried and got stuck" feels like admitting weakness. If your culture punishes that, people will not ask for help. They will either avoid using AI (and fall behind) or use it badly (and create risk).

Creating psychological safety is not "be nice to people." It is:

Leadership visibly admitting what they do not know yet

Creating forums where asking "stupid questions" is normal

Pairing experienced staff with AI-confident staff so both learn

Celebrating good failures ("I tried this approach, it did not work, here is what I learned")

If your culture cannot do that, your team cannot learn fast enough to keep up with AI evolution.

Operations: How you deliver efficiently

This covers your internal processes, systems, and ways of working. How work flows through your organisation. Where bottlenecks exist. How information moves between people and systems.